Ilustrirte Velt (Illustrated World)

Thursday, September 4, 1919

Warsaw, Poland, No. 9

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Translated from the Yiddish by

Mindy Liberman

(Special thanks to Dr. Agnieszka Żółkiewska

of the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw,

and the Central Jewish Library, Poland)

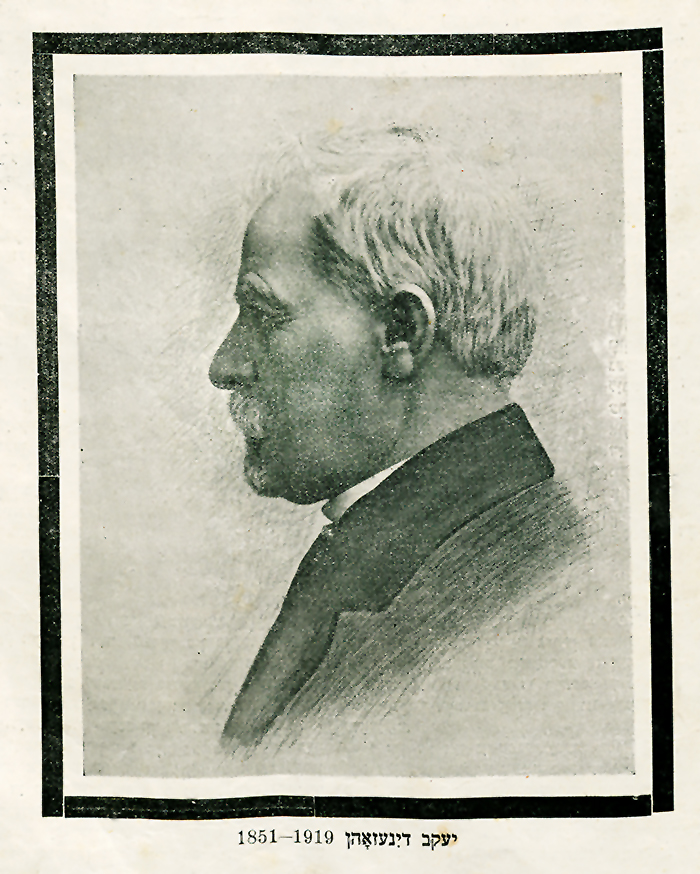

Jacob Dinezon (Pages 129–131)

One of the first who built and created our literature. One of those who stood by her cradle and experienced all the stages of her emergence and development. Almost at the same time as the grandfather Reb Mendele and at a time long before Peretz, Jacob Dinezon began to write for the broad masses in their language. His debut as a writer quickly placed him in the ranks of those lucky ones who engraved themselves in the soul of the people and obtained their eternal love and affection.

In the time of the flowering of Shomer’s “sun and moon novels,” which only stirred up the imagination of the people and transported them to a foreign world that had no connection to the day-to-day reality of Jewish life, along came the eighteen-year-old Dinezon with his Shvartser yungermantshik (Dark Young Man). His name was immortalized not only in the history of our literature but also in the psyche and language of the people. This was the first Yiddish novel with a realistic plot, with natural, lifelike images—with images from the living Yiddish street. For the first time, the Jewish people saw themselves in a literary mirror. For the first time, a writer came along and expressed in words what lay hidden in the depths of their souls, begging to be spoken and revealed, and they came to love the writer.

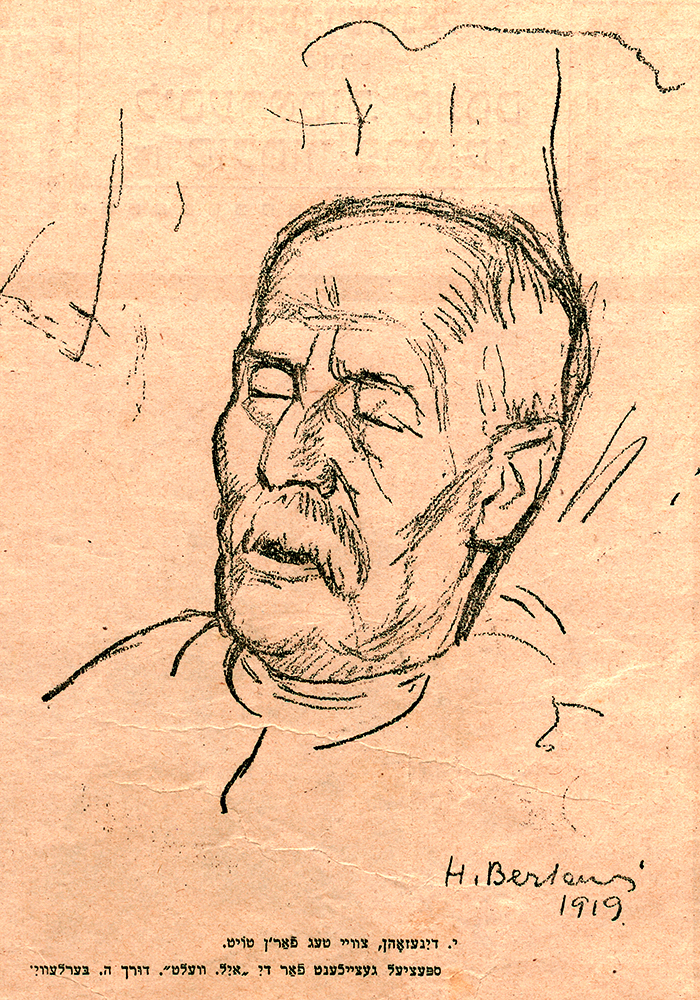

Drawn by the “Ill. World”: H. Berlevi

To that end came one other moment that strengthened and fortified that love even more. Dinezon’s kind, touching, sentimental romanticism was closely bound with a strong ethical feeling. Our mothers and grandmothers were not only moved to tears by the gentle love between two pure young souls and not only cried with the unfortunate hero and heroine over the fate of the beloved martyr—but they also gnashed their teeth at the corrupt dark young man who did not permit the two pure souls any happiness and, according to the custom of that time, was described in the novel as the embodiment of absolute human evil, of absolute black malice.

In this way, Dinezon tugged at the strongest strings of human feeling in the Jewish street of that time. He found such sincere, touching, and soft tones for Jewish love—mute, not yet revealed, not yet put into words. Thus, he expressed so intensely and strongly the keys of human conscience and punished the evil, the wicked so sharply and bitterly.

In this way, right after his debut, Dinezon became one of the most popular Yiddish writers and, in fact, was perhaps the first among us who could boast that the grandmothers, the mothers, and the daughters read him with the same affection, thereby creating a certain literary tradition for us.

And he did not remain standing in one place. After his Shvartser yungermantshik, which remains, as has been said, in the folk-language, as a symbol of everything that is evil, his second major novel, Even negef, which was read no less breathlessly, was published.

From a purely literary standpoint, the second novel has a weaker structure than the first, but there appears a motive that is barely touched on in the first—social injustice. Like the grandfather Reb Mendele, Dinezon not only speaks out here against the wicked but also against the rich and powerful who humiliate and insult the poor small person in his most basic human feelings.

This motive appears even more clearly and in a more artistic form in his later beautifully moving and touching children’s stories Hershele and Yosele that further enhanced Dinezon’s popularity and significance as a writer with a sharper artistic talent for observation, with a warm attitude to human suffering and human tribulations, and especially—with a passionate love for all who suffer and are insulted and oppressed.

After this, Dinezon published other longer works (Alter, Shayke, The Crisis, etc.) in which he even tried to create individual, artistic characters and again demonstrated a fine eye for specific human experiences of Jewish poverty.

This took place together with the upswing of our literature. Di Yunge had already begun to appear, Peretz had fully blossomed, and Mendele and Sholem Aleichem reigned. We already had a secular, multi-branched Yiddish literature—and Dinezon created and wrote and held one of the most honored positions in the Pléiade of the older Yiddish writers. But then came the well-known personal bonding which Dinezon conducted ever after with Peretz—and Dinezon stopped publishing his own work. Not writing, just publishing. This is a psychological puzzle that will undoubtedly be best solved by the memoirs of the departed. Was it a feeling of deep veneration for the fiery, lightning spirit of his great friend? Was it a result of nobler, deeper human thought? It is a fact that during the past ten to fifteen years, the departed brought almost nothing to our literature, although those who were closer to him knew that he wrote and created almost constantly, and the mountain of his writings grew day by day.

After Peretz’s death, which occurred at the height of the storm of the World War, Dinezon took over the great public work that Peretz had begun. He helped considerably to create a standardized model of the Jewish public school. The author of Hershele and Yosele, who demonstrated such a warm feeling for children’s experiences and children’s tears, devoted his last years entirely to the forlorn victims of the worldwide storm. The most moving part of his monumental funeral was just those little Hersheles and Yoseles who accompanied the departed to his eternal rest with the touching inscription “The Beloved Teacher.”

—M.

Condolences (Inside Cover)

Together with all of the friends of our literature we mourn the death of one of its first builders and creators, the generous writer of the people Jacob Dinezon. —The Editors, Illustrated World.

With profound grief and sadness, we stand before the fresh grave of our friend and honorary chairman, the beloved and respected writer of the people Jacob Dinezon. —The Board of the Society of Jewish Writers and Journalists in Warsaw.

With a broken heart, I accompany to his eternal rest my dear brother and friend Jacob Dinezon. —S. An-ski.

With an ache in our hearts, we mourn the passing of our unforgettable, irreplaceable, truly dedicated dear good friend Jacob Dinezon, of blessed memory, with pain and sorrow. —Levi Levin-Epstein and family.

With deep sorrow, we stand before the fresh grave of our dear, beloved, unforgettable elderly friend Jacob Dinezon, of blessed memory. —Union of Yiddish Writers and Journalists in Vilna.

With Jacob Dinezon’s death, Peretz has died once again for me. —Helena Peretz.

Together with all Jewish youth, we bow our heads before our deceased honorary member, creator of Even Negef, Hershele, and Yosele, the self-sacrificing and devoted friend of the Yiddish school movement, Jacob Dinezon, of blessed memory. —Folkist Youth Organization “People’s House.”

A significant portion of the next issue, Illustrated World (No. 10) will be dedicated to the deceased Jacob Dinezon.