Ilustrirte Velt (Illustrated World)

Thursday, September 11, 1919

Warsaw, Poland, No. 10, Pages 151–153

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Translated from the Yiddish by

Mindy Liberman

with assistance from Agnes Romer Segal and Eliezer Segal

(Special thanks to Dr. Agnieszka Żółkiewska

of the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw,

and the Central Jewish Library, Poland)

(Continued from Part II)

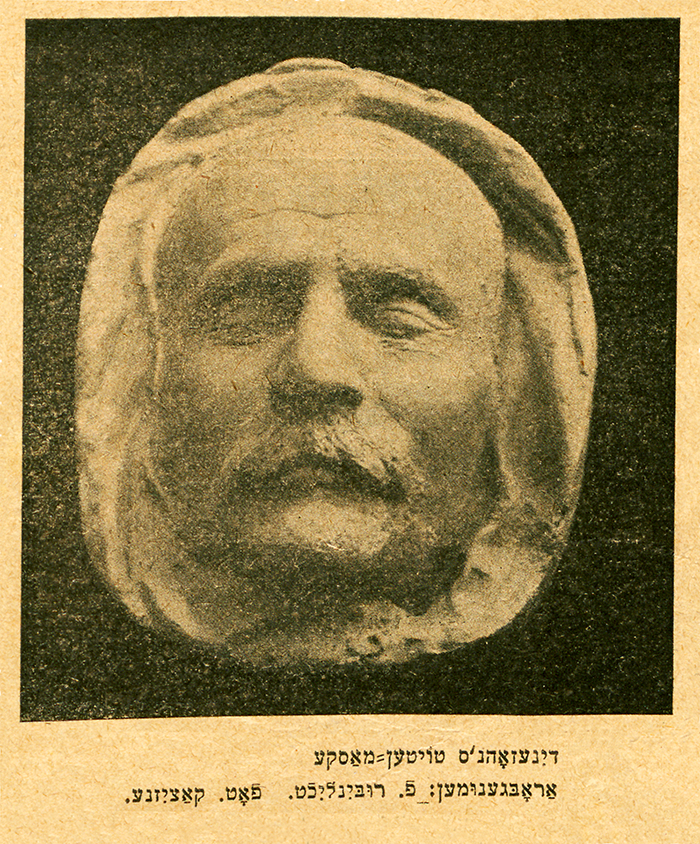

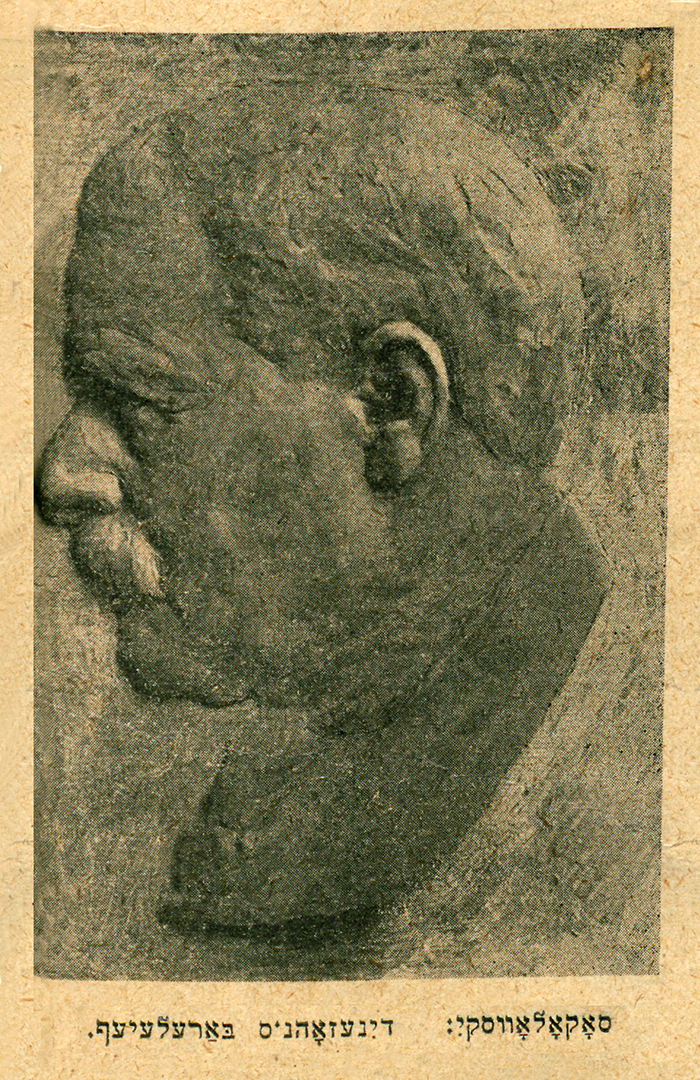

Letters by Jacob Dinezon

First Letter

To My Dear Friend and Companion, Giant of Learning, Luminary of the Exile, Whose Eyes Look Upon the Ends of the Earth and Whose Heart Is in Warsaw, etc., etc., Honor to His Glorious Name, Our Teacher, Rabbi Meir Fried, Known as MYF in the Language of the Gentiles, May His Light Shine.

Like cold water to a tired soul, and like an early fruit before summer, because I was tired and hungry and thirsty, your dear kind letter arrived from the holy kehillah of Orenburg. Tired—of the war in which I had thrown myself since leaving my sister’s shop, and hungry and thirsty because of my loneliness—since you left me, and I have no one to call on when my low spirits become too hard to bear.

Therefore, it won’t surprise you that I let myself be talked into returning to again take up my post as bookkeeper and cashier in my sister’s shop and to live with her as in olden days and in ancient times.

I had thought: Jews are a people; they support so many rebbes, so many rabbis, cantors, preachers, beadles, ritual slaughterers, beggars, and just plain impoverished clergy, maybe they will also support a Yiddish writer. I will write, they will buy my writings, and I will manage to scrape together a livelihood. But I was mistaken! People used to say: “What kind of fool takes a comb to the bathhouse? You can get a comb from someone else.” And now people say: “What kind of fool forks out money for a Yiddish book? You borrow a book from someone, you read it, and you return it.” However, comb manufacturers do more business than Yiddish writers.

Last winter, I did earn something. I wrote fifteen and a half sheets on world history, and for this difficult, diligent work, I received a total of 180 rubles from A., and that was it! To continue to write half for free with the written work belonging permanently to A., as Mr. H. absolutely wishes, I would have to be crazy; I would certainly not do it while sane. Because of the conflict with K., Der yud is closed to me as well. Di velt was ruined even earlier. Some hope remained for America. America, however, is used to reprinting published materials without paying the author even a penny. What did I have left? For the whole summer, I managed to earn maybe 30 rubles for one article in Sefer Ha-Shana. But can you live on that? For my financial affairs with your public prosecutor, Mr. L., you know yourself what a brilliant transaction I made. From 300 rubles cash that I handed to him over a year ago, as of today, I have received barely 118, and naturally, I’ve gobbled it up. The remaining 182 rubles, he says he will pay out when Shtock pays him, and Shtock will pay him when Herzl becomes king in Jerusalem, and Mr. L. becomes his Minister of Finance. But in truth, as little a Zionist as I am, I believe more in the possibility of Herzl’s kingdom in the Land of Israel than in the possibility that L. will become finance minister, even if not precisely in the Land of Israel.

In short, the upshot of our conversation is that Jews are not a people; our literature is a hopeless corpse, lifeless, without the strength to stand on its own feet. Yiddish writers are better off as woodcutters and water carriers, and indeed, they must do that and not wait for a few rolls for breakfast from their literary earnings! If it is so, when the troubles of a Yiddish writer are indeed so great, I said to myself, what do I need this for? Why wait until later? Let me rid myself of such grief! And if I do work, better at my own sister’s than at a stranger’s.

“What has been will be again; there is nothing new under the sun!” It actually pains me very much that I was torn away from World History, in which I became proficient and studied with enthusiasm and diligence, but whose fault is it? Mine or Mr. K.’s?

A gray cloud hangs over Warsaw, damp and cold indoors and out. At a time like this, you want to sleep, cover-up, nestle in, and sleep, and not be aware of anything. And the people do sleep, what a pleasure; they don’t know and don’t want to know what’s going on and what’s new. And really, nothing is going on, and nothing is new. Nothing happened for a few weeks when it was still beautiful and clear out before we had a gray cloud above—and wet, muddy stones beneath—while everything around was still warm and dry. Yes, we began to talk about establishing a society called “Esthetic” here, but because autumn isn’t particularly esthetic, it was better to sleep esthetically under an esthetic quilt, and enough. We hear nothing else about an organization in the Warsaw literary world.

I often ask myself: what would Warsaw have looked like to me had I not had P. in Warsaw? And it’s also difficult to properly imagine how I would have lived with P., and everyone else in Warsaw, had I not had you as well, you, my intimate friend. In addition to our literary bonds, we also have a bonding of souls, and I can talk to and confide in you. Anyone who has experienced loneliness knows how to value a friend, a friend with whom one can speak intimately and with whom one can confide from the heart. However, don’t be arrogant; after all, I need to reprimand you a little. I have a habit of scolding, so I’m telling you to be an observant Jew, not to fail, God forbid, to “read the weekly Torah portion twice in Hebrew and once in Aramaic.” And remember the verse: “Do not be quarrelsome on the way.” Don’t be in a rush, and always write correct addresses to me so that my letters will reach you, not like last time, “Here today, tomorrow he fled.” Do let me know that my notes get to you. I will write to you very happily because I am generally not lazy about writing, and to you I write with pleasure.

I don’t know whether I will yet write anything literary. In the meantime, I write ledgers, revenues, expenses, accounts in debit and credit, notes to merchants, responses to complaints, and complaints without responses.

Second Letter

Peace and All the Best to my Beloved and Cherished Friend, a Neighbor who is Near and a Brother Far off, Who Travels by Sea and Dry Land to Dwell Honorably in the Holy Kehillah of Constantinople of the Turk, etc., etc., My Teacher and Rabbi M. Y. Fried, May his Light Shine.

I had an aunt; she is now gone to the afterlife. Whenever she met someone, she would say, “I’ve calculated that you are actually a close relative!” Reading your letter from the holy kehillah of Constantinople, in which you describe my niece so kindly, I calculate in the meantime that it doesn’t work out at all. The Turk with his wide pants and narrow little fez on his head is not even my third cousin twice removed.

The Turk is a true Mongol, a first cousin of the small yellow Japanese that strikes the Russian soldier, poor thing, with true blows as have not been recorded even in the Yeven Metzulah [a book detailing the gruesome attacks on the Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the 17th-century Chmielnicki Uprising].

You see, Ishmael the Wild Man is indeed our great uncle. This shouldn’t be a disgrace for us, but the Turk isn’t anything more than a kind of Polack of the Mosaic persuasion (?). That is: an Ishmaelite of the Mohamedan persuasion (?). And their master isn’t more than that either. And so, he interests me very little. Even his sleepy navy with its three ships doesn’t interest me, and neither do his dignitaries. And I have been angry, angry even with their great ruler himself for a long time, in that he is such a fool, my goodness, and does not allow the Jews into the Land of Israel. I swear to you, he wouldn’t lose anything by it, and as he doesn’t understand this, and lets himself be gobbled up by Austria and other hungry gobblers. It serves him right, the devil take him.

I would really be a lot happier had you written that you’ve made a good start on your venture. “Business before everything else!” says the American, may he live long. There’s a strong fellow! A twist, a turn, the ground burns beneath him, the sky flashes over his head, and what he accomplishes in one day, one of us couldn’t get done in a lifetime. I describe the good qualities of this young man to you for the same reason that King Solomon, may peace be upon him, said, “Go to the ant, you sluggard! Consider her ways and be wise!” Well, Solomon, may he forgive me, was foolish in that he worked with an idler. Had he been smarter, he would have known that the idler would have been too lazy to go to the ant and would learn nothing from her. However, as you know, I am smarter than he who was smarter than Eitan the Ezrachi, than Heman, and than Darda, and I tell you, my esteemed Mr. Fried, do not be lazy, but learn to do business from the American.

Let him sleep; let him enjoy his earthly rewards in his harem; I don’t begrudge him in the least. I’m not even jealous of his little mountains of garbage under the doors, his dogs in the streets, and his living merchandise in the bath, in the poorhouse, and in the holy place, I beg to make a distinction between them. I’m only jealous of the Russian soldier. He takes in more in one day than a hundred merchants during the entire fair. He collected from the very beginning, collects right up to today, and will, with the help of God, blessed is His name, continue to collect. On the other hand, how does the Little Turk like Russia’s earnings in Mukden? And here in Warsaw, it’s merry. They shoot day in, day out, and they simply don’t stop shooting. Yesterday on my street Dzielna, and on Karmelitska, Djika, Gensha, and Nalewki, there was quite a wedding.

And the story went like this: a Jewish laborer, who had been arrested, died in Pawiak Prison. For this reason, masses of laborers gathered on Dzielna and Djika Streets to attend the funeral. They didn’t disturb anyone all day. There was no sign of police or a patrol. They stood quietly and respectfully waiting for the coffin to emerge from Pawiak so they could go to the funeral. Suddenly, however, at six in the evening, cavalry with a whole company of soldiers rose as if out of the ground and soon fired volley after volley with no reason. They killed eighteen Jews with no chance to say confession. Masses of them were wounded, and, as happens in our camp, all were innocent, poor things, old Jews and small children. In one word, everything according to custom, and go protest in vain!

And not a day, not an hour passes without such pointless sacrifices with no justice and no accounting. What a time we live now in Warsaw! And there are fools who look to the sky and think: soon, soon the sun will shine, and there will be a warm, bright spring on the street. And the sun will also shine into our Jewish windows. Fools have faith; the gullible believe everything. However, anyone with a hint of a brain in his head can see the heavy dark clouds that hang even now over our heads and those even heavier and blacker that roll in from the north and will extinguish the light completely. The bureaucracy, as we now call that widespread plague, treats the Russian public as a small child that allows himself to be taken in, to keep quiet with the promise of a small cake, even though the nanny is cleverer and devours the promised cake herself. They promise gold mountains, fine stones, and pearls, but when the child screams: “Give them to me for once!” they answer that Mama has gone shopping and the cake is still baking at the baker’s, or the cake has already been baked and Mama has gone to sell the cake for a few groschen. And after all these promises and excuses, it always turns out that the dog has snatched the cake and gobbled it up, and—no more cake!

“Commissions” sprout among us like pine trees in Otwock. Some commissions soon become pregnant and, with any luck, beget twins and triplets—new commissions. So on until the end of all generations, and all because of the promised cake, which the nanny herself will ultimately devour, saying: “The dog snatched it, and the cake is no more!” Remember what I tell you: “The nanny is a glutton and a drunk and a nibbler, and woe to the child she tends.” No one denies that our bureaucracy has a great appetite that will never be satisfied, and woe to us if we still hope that it will give us anything!

There where you are now is not Constantinople, not Turkish. Here in clean, paved Warsaw, you can see legendary Constantinople with its beautiful legendary Turkish economy and bright civilization . . . You see Armenians in your Constantinople. Do they slaughter them? Do they shoot them in the streets as they do here in the so-called European city of Baku? Do they attack a crowd of Jews there, whether just people, university students, high schoolers, or plain intellectuals, and one, two, three, they’ve been shot, killed, wounded—and then silence?

The Constantinople mountains of trash under the doors don’t appeal to you. And do you prefer that one choose for himself a dignified death on a clean paved street? Anyone who laughs at the Turk and boasts about this European order isn’t worth any more than a “dignified death” himself!

I can’t talk about anything without quickly coming to politics these days. If I just want to write a note about a pound of soap even, or about a herring in a little cream, a few words about the Zemsky Sobor [the Russian Assembly of the Land], freedom and justice get mixed in even though I believe in all this as much as I do in Rabbah Bar Bar Hannah’s stories in the chapter about the boat seller in Bava Batra.

You have undoubtedly read Andreyev’s The Red Laugh. His main characters all lost their sanity because of the war in Manchuria. You can go crazy even more quickly from everything that is happening here.

P.S. Be so kind and find out from the Turk how this is written: the way Dr. Luria writes “Turkishi” or “Turkishe” as Peretz wishes? Constantinople is undoubtedly capable of deciding this important question.

Handwritten Letter

Dear Friends Sholem Asch, Reyzen, and Pinski—

An inheritance has been left to us from our beloved Peretz: “the children’s home” for destitute Jewish children that he established before his death with the help of the Saint Petersburg (?) (?) Society. Peretz is no longer here. I have taken over the home, dear to him, and bear the burden for him alone. I ask: why, friends, do you allow me to carry out this holy duty alone for the deceased teacher and for the living orphans in his home? Do in America what you can to collect the means to maintain the home. Funds are lacking; devotion and care are not lacking as long as I am alive.

Your Dinezon.