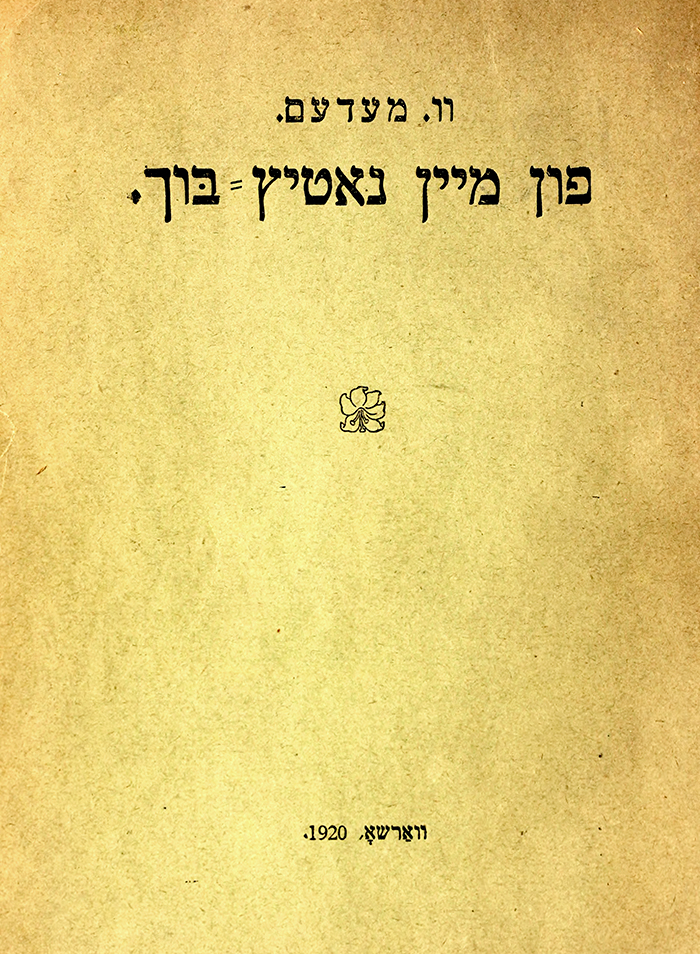

By V. Medem

From Fun mayn natits-bukh

(From My Notebook)

(See Yiddish Version Here)

Warsaw: O. Rom, 1920, Pages 123–130

Translated from the Yiddish by

Mindy Liberman

They say that a person dies, but his work remains.

A small consolation. Because the most precious thing we have of someone who has died is not what he has done but what he was—the living individual personality.

Dinezon has died. His books remain and stand on the bookshelf. His children’s homes remain and will hopefully not fail. That is important and precious. But for me—and I also believe for everyone who knew and loved him personally—that is not what is most important and precious.

Precious and dear to me was the person. That old man with his white hair, with his quiet voice, with his sweet “Vilna” pronunciation, with his dear smile, with his kind talk. And the most precious and greatest treasure: that beautiful, pure, characteristic soul that was simply mirrored and reflected in his exterior features.

And as always, when one stands before the fresh grave of someone one has loved, one feels the burning desire: how to ensure that the most important and precious things he gave us are not lost? And one wants every significant person to have an artist to make his physical appearance everlasting and a wordsmith to make his soul eternal. To make it eternal and thereby grant it to live on, with and in the existing generation and future generations forever.

I am not that artist. I will contribute no more than a few small, modest traits to preserve a portion of the precious legacy.

Legend has it that Elijah the Prophet dwelled in the desert for forty days and forty nights. A storm rose with thunder and lightning. But not in the storm and not in the thunder was God’s voice heard. A whirlwind arose, angry, wild. And God was also not in the whirlwind. But suddenly, a great, holy stillness came to pass. And in the stillness, the prophet finally heard the voice of his God.

So the legend has it. How far from this is the great, gray Jewish public at large! And how far from this public is the great, holy stillness!

The Jew shouts. The Jew shouts when he is happy and shouts when he suffers. He shouts when he begs God for mercy and shouts when he laments and expresses gratitude. The Jew shouts and makes a commotion. Do not think that this is the stormy anger of a fighting nature. It is another kind of commotion.

The Jew has no respect. I don’t mean the kind of respect drummed into us in our childhood years, in synagogue, in school, in society: be obedient, mind your parents, bow and scrape before the nobleman. Oh, the Jew possesses more than enough of that kind of respect.

I mean something else: there is a German word: “pietät.”

It can’t even be translated into Yiddish (where something itself is lacking, the word is lacking as well.) It’s not ordinary respect. It’s respect for holiness combined with love and quiet, caring concern. That’s what the ordinary Jew lacks, and that’s what a person needs to have. For there are holinesses in life and in the human soul, and every person must have his Holy of Holies. And one enters the Holy of Holies with quiet footsteps, with downcast eyes, and with closed lips.

Do I have to tell you that I don’t mean this in a religious, mystical sense? You understand that on your own. That holiness can be, for example, a social ideal, it can be love, it can be friendship, and so on and so on.

The Jewish public lacks this. His cry is an expression of familiarity. He addresses everyone in a familiar way. He touches everything with his hands. Even with the Master of the Universe himself (which should certainly be something holy for religious Jews), he speaks as if to an equal. He haggles with him, schemes with him, tricks him. Even for death, he has no respect. Even in the cemetery, he doesn’t cease making a commotion . . .

In what connection do I say this? So that we’ll better understand what we have lost with Dinezon’s death. Because he was no less than one of those few Jews who possessed that great, rare quality.

In the midst of the petty commotion of life, in the midst of the tumultuous world of literature that shouts even louder, rants even more, and is even more brazen than all the rest, he remained quiet, pure, and refined. A white dove among the black crows and conceited, false peacocks. A quiet, pure person. A person in whose heart lived gentle, warm, bright holiness.

Remember his friendship with Peretz. Not for nothing did Peretz’s widow write these moving, profound words: “With Dinezon’s death, Peretz has died for me a second time,” because it really was that rare a friendship when two become one. He who can be that kind of friend has in his soul a Holy of Holies.

And his love for the children. Loving children the way Dinezon loved them is really a sign of quiet nobility. This love ran through his life like a red thread, beginning with Yosele, about whom he wrote, and ending with the hundred Yoseles for whom he cared. It’s not an accident because he had within him a bit of a child’s soul, a simple childish purity.

And the soul of a child still has that great love-respect that I spoke about earlier. The soul of a child holds within it the quiet purity and holiness with which it shines on the world around it, with which it lights up and ennobles all of us—we who need it so ardently and painfully.

The elderly, gray-haired Dinezon possessed that childlike soul. “We didn’t notice him,” An-ski lamented bitterly at the open grave. “We notice those who take and not those who give,” and we are left with a debt that has not been repaid. Now he is gone. And only now will we undertake to repay the old, large debt. Not as a dry obligation but as a deep internal desire, and because our lives have a need for this. Our dark lives, our crippled lives, our petty lives need this so that the treasure of a beautiful, pure, and healthy person will not be lost. Our lives need the legacy to be preserved, to pass over to our flesh and blood.”

And we will breathe in the quiet, pure refinement and carry it in our souls from generation to generation.

We did not carry flowers to Jacob Dinezon’s grave. We wanted to make the funeral as simple and modest as the person himself was simple and modest. Let these few human words, written with love, interwoven with grief, carried with gentleness and care, be lowered now as a wreath from me onto the dear, fresh grave.

September 3, 1919