By Jacob Dinezon

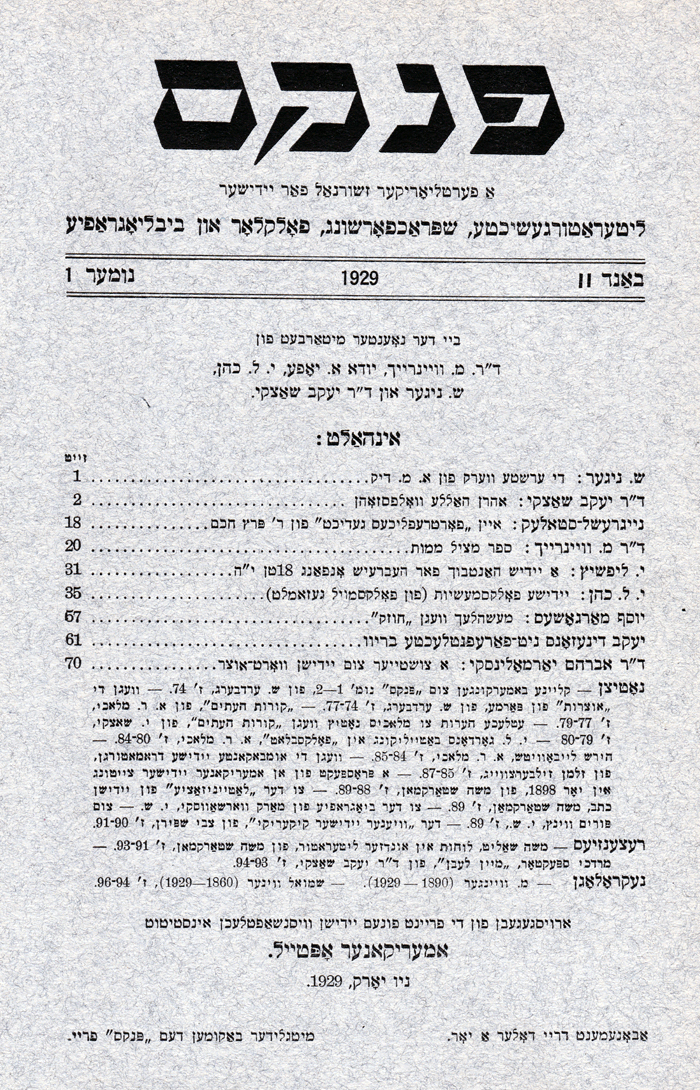

From Pinkes: A Fertlioriker Zshurnal far Yidisher Literaturgeshikhte, Shprakhforshung, Folklor un Bibliografie

(Notebook: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Study of Yiddish Literature, Language, Folklore and Bibliography)

Presented by Dr. Yakov Shatzky

New York: The Yiddish Scientific Institute, 1929,

Vol. 2, No. 1, Pages 61–69

Translated from the Yiddish by

Janie Respitz

This long letter, which we are now publishing, was written on July 31st, 1909.

Besides its value as a psychography of the author of The Dark Young Man, this letter is an important source in the biography of I. L. Peretz.

We have before us an exhaustive, authentic description of Peretz’s family tragedy. Lately, there has been a lot written about the family issues of this great writer. Roza Lax-Peretz (in World of Books, Literarish Bleter, and the Forverts), Zvi Hirshkon (in Farband of Polish Jews, Tzukunft, and the Forverts), and others have described the relationships between Peretz, his only son, daughter-in-law, and grandchild.

The section on Peretz in Dinzon’s letter is perhaps the most detailed description we have of this painful issue, which is, without a doubt, very important in the biography and psychography of I. L. Peretz.

The letter is published here in its original spelling, however, the punctuation has been improved.

The original can be found in the possession of a family who were friends for many years with Yakov Dinezon.

The first letter was published in Pinkes, vol. 4, pp. 377-380, and other letters in the subsequent volumes of Pinkes.

At this opportunity, I feel it is my obligation to express warm thanks to the possessors of this correspondence with Dinezon for their kind permission to publish these interesting and important letters.

For the characteristics of Dinezon the letter-writer, see Sh. Niger’s article in the American Shriftn (Writings) (Autumn, 1919, Section VI, pp. 26-28).

Warsaw, Friday, July 31, 1909

To my best and most beloved good friend Mirele!

Two friends who only wish each other joy and pleasure cannot avoid the unneglected and inadmissible self-suffering which they create for themselves precisely because of their friendship.

With my entire being, I always want to comfort you, my gentle beloved Mirele, and bring you great pleasure, but then, you, my dear, darling friend, begin to feel sick and suffer because of me.

You just had two weeks of pure anxiety and suffering caused by your Dinezon’s silence when his words were perhaps even more necessary and awaited than ever.

I do not know why things cannot be different; I only know that it hurts me.

I received your postcard, which said how anxious you were about my not having written, and I could not even respond to your postcard to tell you not to be so upset. I received your telegram but could not say more than a few words as I had already written to you the day before. The day after I received your telegram, I received another postcard, which hurt me even more as I saw you were suffering even more because of me, because of my pure loyal friendship to you, which is more loving and satisfying than anything.

Mirele, look how no light can be overshadowed, just as there can be no pleasure without pain and suffering.

Do not doubt my pure and sacred love for you. I have convinced myself that you believe me when I say that in a situation where I can comfort you and bring you joy, no sacrifice would be too great. And I also believe you, my dearest devoted friend, and subsequently, how much resentment and suffering do we both feel against our best wishes since we became dear friends. Did God actually create night and darkness so His creations would enjoy daytime and light even more? Good and bad are mixed together, and we must be able to understand the difference as in many books on moral instruction, Jewish and non-Jewish, that want to explain everything about nature.

I do not know, dear Mirele! I only know that the dearest friendship often has its things that are unacceptable, and the purest ideal love has its package of pain and suffering.

If I were not such a friend, you would not be so upset when a letter from me arrived late once in a while. If I did not love you so passionately, purely, and sacredly, I would not be so upset when I could not write to you whenever I wanted, and I would not feel so morally dejected. I say: morally, because besides what my soul suffers, when I don’t write to you, I become anxious, with resentment and pain, and all I do that is morally good is not recognized.

Forgive me, my dear beloved friend, for the pain my not having written has caused you. Our power and time are being weighed and measured at this moment and will only strengthen our never-ending friendship.

One more thing I would like you to believe. Your Dinezon will never, of his own will, cause you pain, and never will his love cool nor his devotion lessen. And if it happens that a letter from me will arrive a day late or maybe a few days late, you, my good smart friend, should not seek to blame, neither me nor yourself. I will never blame you, and you should not either, even if, at times, you want to. This is how well I know you, how much I believe you, and how much I love you.

I wish, with my entire soul, that you understand this and not just take my word for it.

And if you understand, I hope that a missing letter from me will not cause you such unnecessary suffering as it has this time.

Give me your loving devoted hand as a sign that you promise, and my conscience will be calmed by your promise.

I already told you why I did not write to you last week, my dear friend. I want to tell you now why I did not even write a postcard this week and only wrote a few words in a telegram:

Monday, late at night, I was called to my nephew’s who is in Warsaw from St. Petersburg and is staying in a hotel. I was told to go right away as he was feeling very, very bad. Of course, I immediately assumed my nephew had brought Cholera with him from St. Petersburg. On my way to see him, I stopped at a doctor who is an acquaintance of mine and brought him with me. The doctor did not find any Cholera symptoms in our guest from St. Petersburg, but he was convinced by the symptoms he did find that he had an inflammation no less serious than the St. Petersburg Cholera. [Translator’s note: the disease here is called Blind-Darem; I could not find a translation.]

Why, Mirele, should I pain you, telling you about my angst, fear, and effort spent the entire week on this patient? Better I should tell you that my efforts were not futile. Thank God he overcame the danger, and my nephew now only needs a few days of bed rest.

There is no longer any reason to fear for his life.

So that’s how it is, my dear friend Mirele, do not feel neglected. It cannot be any different in our lives. What did Miss Frank[1] say in her Yiddish letter to me? “Dear friends have the same right to share their suffering and joy.”

And she is right. Friends should not only be obligated but should also have the right to share their suffering.

The joy we share with our friends does not give us the right to share our pain. The joy which people feel can never be so deep and intimate as our pain. How does the expression go: “When you laugh, everyone sees; when you cry, no one sees.” In order to share one’s pain with a friend, one must be intimate, and to be intimate, you must have a certain right.

You, dear Mirele, are intimate with me. Like a devoted sister, you have told me much about your intimate life, and I, therefore, have the right to share in your suffering as I also wish to share in your joys. My greatest wish is for you to feel as intimate with me as I do with you, but you are ashamed of something. Whenever you want to know something about my intimate life, you excuse yourself and ask if you have the right to ask. Nevertheless, you do share in my suffering and with great devotion.

You shared my anxiety without knowing why you were so anxious.

Let this sad fact alone convince you that you have the full right to share in my suffering because you are my most beloved, devoted, intimate friend.

This nephew of mine is my sister’s son, who sadly died young last year on the second day of Rosh Hashana in Konigsberg. She was 42 years old. She was a widow for twelve years with two small boys from her beloved husband. She did not want to remarry because of her children. The older one is 19 and graduated gymnasia (high school). After his mother died, he abandoned further studies and took over the business which he inherited from his mother. The business is going very well. The younger brother is now in the fifth class in gymnasia in Pernov, Lipliand province. These lonely children do not need any financial aid as their mother left some capital and a well-run business in St. Petersburg. However, they are both young and lonely, without a mother or father, and it is my sacred obligation to make them feel less lonely.

Therefore, dear Mirele, you can imagine the painful angst I have been feeling over the past few days until the doctor assured me the danger of his illness had passed.

Unfortunately, this time, my nephew stayed in a hotel, and the doctor forbid me to move him to my home because with this illness, the slightest movement could be dangerous.

Now Mirele, do you understand why I did not write all week even though I knew very well, and it hurt me that you were feeling anxious? Please forgive me, my good, devoted friend; it could not have been any other way. If friends want to enjoy one another’s pleasures, they must also share their suffering, as there is no joy without pain. And I wish and hope, when I think of your situation, that you won’t be without joy in the future, my dear beloved Mirele.

I ask you, do not lose hope for good things and happiness. Throw away your sick pessimism, live, enjoy life as much as you can possibly enjoy, and hope for better and happier days as well as years.

I am more than twice your age, my good dear friend, and have had a lot of pain and suffering. I am not telling you my suffering has been worse than yours, but I have suffered more since the longer you live, the more you suffer. Nevertheless, I do not live one day without hope, with the comfort of knowing that one day things will be better. This gives me courage and strength to live, to love life, to love people, to love the world, love them as they are, the people with their meanness, and the world with its dirt and mud . . .

I write these words to you, my best beloved friend, after your words left a deep impression on me: that you are indifferent toward death and you fear life.

Mirele, these words of yours and what you tell me are affecting my well-being. I ask you, if you are really so indifferent toward death, I hope it is not because of me! Because of me, Mirele, you should want to live and be happy. Do you not know how much I love you? Do you not know that those who love you are a part of your life? You may laugh at me, but the truth is, since I met you through our letters and began to love you, my life has become more loving, sweet, and interesting. How can you love me and still be indifferent toward death? Don’t do this, Mirele. Let me be happy with your joy. Let me enjoy future happiness from knowing that you are happy. No. You must not make light of my endless love. Your health is dear to me, your happiness, your life! Without life, Mirele, there is no soul, no spirit, no intelligence, no talent, no charm, no friendship, and, of course, no love.

Unless you don’t love anyone, not your highly respected parents, nor your beautiful children, the two innocent angels as you call them, nor your illustrious, talented brother with his gentle brotherly feelings for you, and your love for me, your devoted friend Dinezon, also not for his pure, true, ideally sacred, friendly love, not even my Bieltze and my Paylitze[2], who are worthy of your love.

Is this good on your part?

Tell me yourself. This time I don’t know how to defend or justify your words. I do know that when I really love someone, I love my life because of them. I also love the pain and suffering life brings me.

I received your third postcard this week. A week of postcards and not one letter from you. But your cards are also precious to me, and I thank you for them as well. They have their own special charm and stir up my soul. I don’t know why but they never quell my passionate thirst to talk to you longer or as much as possible in a postcard.

But you do mention a certain chutzpah (nerve or insolence) in your postcard because of your telegram. God in heaven! Do you really not know me? Do you really not understand me or our friendship?

There can be no talk of chutzpah among true friends. Your telegram simply stirred me. It convinced me that I am not an incidental friend but something more. If you cannot accept his not writing to you as before, then I don’t, on the contrary, have to thank you and am obliged to find insolence in your words.

Oh Mirele, Mirele, how much longer will you feel like I am a stranger? How much longer will I be the Dinezon you know from his “Stumbling Stone” and not the Dinezon who feels so close, so akin to you, and has never felt so close to anyone else his whole life?

How many times have I asked you to be my friend? [Translator’s note: here Dinezon uses the Hebrew word khaver, in masculine form for the first time for friend and not the feminine frayndine.] You yourself cannot doubt that I only wish the best for you. I only wish that when you write to me, when you speak to me, you should express yourself freely, comfortably, and feel as if you are talking to a friend, with a brother, and nothing more. I do not understand why you don’t feel this way, or perhaps you just can’t feel it?

“A Rebbe,” you say. Yes, that’s what you want me to be, and you want to be afraid of me. However, being a friend with your soul equal to my lonely soul is something you don’t want or can’t do, and I absolutely cannot understand this.

This could mean one of two things. Either you place me too high, and you feel inferior and do not feel you are my equal, or your understanding of what I mean by friend, which I can only explain in words is, forgive me, incorrect and untrue. In both cases, Mirele, you are mistaken. I am not any higher than you or anyone else. When I use the word friend, I mean nothing more than we are equal, you should consider me as a brother, and you should not feel anything artificial toward me as you would to someone you just met a few months ago. Believe me, the moment this happens, I will no longer feel in your writing a trace of forced or strained words but rather your free and natural words. I will be delighted! You speak about being afraid of me, about something about me that makes you anxious? This really hurts me, my love, and I know you do not want to hurt me, but it happens from your feeling that I am a stranger.

You might say this is an old complaint. Yes, it is my old complaint, but it will remain if you continue to feel like this.

And you want to have a connection to me. My beloved Peretz’s son, who is sitting with me now as I write these words, is a son-in-law of Shloimele Ayzman (the brother-in-law of the local Hasidic millionaire Shaye Prives. They are both no longer alive). And I can tell you that Peretz’s son divorced his illustrious wife long ago, which means you and I are also in-laws, and I still feel like a stranger to you?

Listen Mirele, if this interests you. Twelve years ago, Peretz, the father, told me that Lucian, that’s his son’s name, was in love, but he, Peretz his father, did not know with whom. Therefore, he asked me to go to Lucian.

This Lucian Peretz is the only child Peretz has. He had him, this Lucian, with his first wife, whom he barely lived with for a year after their wedding when they divorced. Although the father of his first wife was the famous Jewish mathematician Lichtenfeld, from the old Jewish educated freethinkers, and Peretz was his student, Lichtenfeld’s daughter was too fanatically religious and could not tolerate Peretz’s radical non-religiousness. After she gave birth to their only son, they divorced. Peretz took the child, and they both remarried that same year. She married a pious Hasidic Jew according to her liking with whom she lives happily, and had a few children. Peretz married his present wife, with whom he has been living for 28 years, but they did not have any children together. His present wife raised his son as a mother, but he never felt towards her how a child from early childhood on feels toward his own mother. He didn’t only feel this way toward his stepmother but his father as well. Why was it like this? The son himself cannot explain it. Neither can Peretz nor his wife. Peretz is a passionate, gentle father and loves his son very much. His wife did more for her stepson than a mother would do, but he remained alienated, never exchanging intimate words with them. It is still like this today even though he lives with them and eats at the same table. If Peretz needs something from his own son, he asks me to go to him. I am lucky. He tells me everything and can spend entire days with me. He is very well educated. He graduated from the faculty of mathematics at the University of Warsaw. He’s very well-read and honest with a fine disposition. He does not speak a word of Yiddish and does not understand when spoken to in Yiddish.

This is the curse of the former Enlightened Jews, Maskilim. The first Maskilim, Hebrew writers and poets, they should forgive me, spoke, wrote, and sang in the Holy Tongue but did not even teach their children the Hebrew alphabet. This was true with Mapu’s children, Slonimsk’s, Smolenskin’s, Gordon’s, Sokolov’s, and, unfortunately, also our intelligent Peretz, with his rich Yiddish heart. He taught his son German, French, and English, but not Yiddish. His only son could never read a single word of what he wrote in Yiddish.

In truth, the main reason for the young Peretz’s alienated feelings for his own dear father lies in his psyche, that is to say, in his nature and being. This is called: “A zonderling,” one who runs away from people, although he does not hate them or, simply said in Yiddish: a bit of madness. He can go for months without uttering a word at home. If Peretz would have provided him with a natural education, his child, even with his madness, would not have felt so alienated and cold in his own father’s house.

What I call a natural education is the first and only education parents are obligated to give their children so the child does not feel alienated and they do not remain strangers. This is a natural nationalist education that connects people not only with blood ties but also with their traditions. Can a person feel Jewish when there is not even a single drop of Jewish education in his childhood, and he was never taught Yiddish in his childhood? His connection to his parents is therefore strange and unnatural, not knowing the minimum of what Judaism means and what connection his parents and relatives have to Judaism.

The same occurs when a Russian educates his child with German teachers in German culture and language and makes sure he is not corrupted by a Russian word or a Russian custom. This is what our former Maskilim did with their children, protecting them from Yiddish words and Yiddish customs, which God forbid they should learn about. And the Russian and German are not as far removed from one another as the Christian is from the Jew. This was not so rare or out of the ordinary. Unfortunately, this occurred often throughout the diaspora. It is no wonder that the curse emerged:

“Your sons and daughters will be given to another nation, and you will wear out your eyes watching for them day after day, powerless to lift a hand.” [Translator’s note: Deuteronomy 28:32.]

Jewish parents cannot derive pleasure from such children if they did not provide them with a Jewish education from early childhood and the same cultural and world outlook.

But this has nothing to do with the plot of my story. I just mentioned it because this is a painful wound for our people, which hurts me very much as a Jew. And I can’t not express my feelings even in passing. Forgive me, dear Mirele, you are probably used to my unsystematic way of speaking to you, and you do not demand my letters to you be written in any order, divided into chapters, as I would do in one of my works or articles. For you, my dear, heartfelt friend, I can speak my thoughts as they swell in my mind and heart, unpolished and disorganized, and you understand, as a devoted friend, not true?

And I learned from the young Peretz what his ideal is. He presented it to me. It is the great, rich, Warsaw Jew Shloime Ayznman’s youngest daughter, Helena. Although she is not the daughter of a Maskil, she has less Jewish education than her beloved, the young Peretz.

Reb Shloimele, a true Hasid, himself far removed from education in general and particularly from European Christian culture, gave all his daughters a pure Christian education without the smallest trace or connection to Jews and Judaism. As a result, a few of his daughters were poisoned and ruined, perhaps because they were able to convert or fell in love with young men from much lower families and immediately regretted the wedding. None of Ayznman’s daughters were happy.

Helenka, young Peretz’s fiancée, as he introduced her, was very smart and nice, well-educated and kind. She was madly in love with the young Peretz. She would try to convince me of her love for him, although I clearly explained the seriousness of her decision, going against her father’s will, as well as not denying the odd behavior and humorous pranks of her beloved, which could continue for the rest of his life and could perhaps become worse. Her future father-in-law, Peretz, told her the same thing. We could only tell her the truth as we could not see any great joy coming from this bond. We noticed that she, his love, was also a bit crazy, and two people with their individual craziness could not last long together. They, of course, did not want to hear the truth from us, and one cold winter evening, they were married in Peretz’s house by a rabbi with all the ceremony of a Jewish wedding according to Moses and the people of Israel. However, neither his father nor any members of the Ayznman family attended the wedding ceremony.

They lived together for a few years, and it became obvious that things were not great between them. A child was born, a boy, and the old man Ayznman said if they decided to raise their son as a Jew, he would come to the circumcision and make peace with the young couple. He prevailed. The circumcision ceremony was actually quite nice, with new Jewish dishes as pious Jews would do for Passover. The pious Ayznman’s daughter did not want a Jewish kitchen, but young Peretz did not see it as a drawback. He was not, in spite of everything, a Gentile.

This is how they lived for five whole years. We loved her, even though she was a bit crazy; she had a good soul and was also smart. But one fine morning, young Peretz came to his father and informed him that from that moment, he was returning to his father. Earlier, they lived, young Peretz and his parents, next door in one building down the same corridor. Later, husband and wife also wanted to live in the same building, she in her apartment, and he in his father’s apartment. This is how it was for two years. A stranger would have never noticed that husband and wife lived in two separate apartments. She would come to her father-in-law’s around ten times a day, and we would go to her as we did before. But husband and wife were estranged and did not exchange a single word for two years, even though they would see each other ten times a day. We knew they had some sort of a conflict between them, and they agreed to divorce. What the conflict was, we could not find out, not from him and not from her. We did know that the old man Ayznman was against divorce. “I did not agree to the wedding,” he said, “but it happened without my consent. Now, especially because there is a child, I cannot permit a divorce.” And as long as the old man lived, the divorce was not carried out. Soon after his death, they divorced. But she did not give the child to her ex-husband. Mine and Peretz’s relations with her are the same. At times she comes to me, and sometimes I go to her. She also meets her former father-in-law with the same friendliness as before. However, she does not come to Peretz’s home, as apparently, she does not want to see her former husband.

Once I even tried telling her that for the sake of the child who is torn between his mother and father, and he already understands that this is not natural, they should get back together. But then she asked me with tears in her eyes not to talk about this again as the sky and earth cannot come together. What was broken cannot be fixed, and she is sticking to her decision.

Neither he nor she married again. She brings the child often to his father, bringing him to the gate of the house where Peretz lives. The child remains with his father for a few days, and when he misses his mother, his father takes him to the gate where his mother lives.

And this, dear Mirele, is how the quiet tragedy is played out in the family life of many families and homes here, there, and everywhere. And in your family tragedy, you are not the one and only daughter. In “good Jewish” families, there is no shortage of tragedy. But about this, you know more than I do.

I told you the story of young Peretz here in confidence. Please do not tell this story to anyone.

Also, in the life of the serious and worthy Helena Frank, there must be a deep tragedy about which I know nothing. I could not be impolite and ask about it, and she does not tell me on her own. In the many phrases and expressions in her letters to me, I feel her wounded heart and her deep suffering because of it. As she told me, just like you did, dear Mirele, the deep impression that was made on her non-Jewish soul (as she wrote, “my non-Jewish soul”) when they told her about me, that I was unmarried and did not know about family joy. “Apparently a person’s heart,” she wrote to me, “is the same among the richest and the poorest, and what you can’t find here, you can’t find there either, as one may think. I do not feel sorry for you, and you should not feel sorry for me . . .”

As for befriending the two of you, we must be patient. In her last letter, she wrote that she feels very weak and dejected and is counting the days until she can take a trip on the sea to distract herself for a few months and she asked me not to think badly of her because if I did our letter writing should cease for a while. For that reason, she promised me she would write and tell me about all the beautiful and interesting things she would see on her trip.

About her coming to see me in Warsaw, she once sent me an illustration of a test made in London of a flying machine and wrote the following words: “Until now, I was an expert at flying to my love but only in my fantasies. Now I am starting to believe that it may be possible in our lifetime to fly to you in Warsaw. Tell me, would I be a beloved guest?”

She often mentions her beloved flying machines in her letters and tells me how she wants to come to Warsaw in such a machine and be a beloved guest, talk to me in Yiddish, and I can get to know her and understand her better. She says she understands me very well and wishes that I can understand her as deeply.

So, my beloved Mirele, today, when I thought I was going to write only a few words to you, I wasted a lot of time chatting and wrote an entire megillah (a long story), and I myself don’t know where I left off. You are probably tired of reading my megillah, but I am far from being tired of writing to you. This is the power you have over me, my beloved Mirele. When I write to you, a stream opens, and I forget where I am in the world and in time. I even forget that perhaps you are tired of reading as I let my pen go free, and it seems to me my pen is indifferent. It runs over the pages as if carried by a good angel, and I don’t even notice that page after page is filled with writing. Tell me, Mirele, why does my pen also love you so much? Why is it so attracted to you and never tires?

So, my dear, it appears, according to you, we are actually connected through the story I told you about young Peretz and his former wife. Does this annoy you? Do not be annoyed, my good one, my dear. Do not forget what you yourself wrote to me in your first beautiful letter: “A strange type of relationship, I feel a warm feeling of closeness to you, which gives me courage to write to you!”

Remember dear Mirele, your own serious words to me? I do not forget them for one minute, and I’m not looking for another relationship, no transformations. For me, it is enough to feel your closeness and kinship, and we will remain the two devoted dear friends that we are for the rest of our lives.

Send my regards to our dear [illegible], and your beloved brother whom I love as well . . . and for all the blessings you send me, I send you one blessing: you should be healthy and truly happy.

Give me your hand and let me warmly hold it with my entire soul and heart. Your loving,

Y. Dinezon