In 1906, Johan Paley, the editor of the New York Yiddish newspaper, the Jewish Daily News, sent Jacob Dinezon a telegram inviting him to America. Along with the telegram, Palely sent a first class ticket on an ocean liner. Perhaps Paley hoped to recreate the excitement generated by the Yiddish humorist, Sholem Aleichem, who visited America a year earlier. Like his friend and colleague, Dinezon was well-known in America. Editions of his novels, including The Dark Young Man, Hershele, and Yosele, had been released by New York publishers, and he was a frequent contributor to American Yiddish newspapers.

Dinezon’s reply, however, dashed Paley’s plans. Written in the aftermath of the failed Russian revolution of 1905, Dinezon’s letter shows his courage and commitment to remaining in Poland during a violent and trying time.

As Russian soldiers patrolled the Jewish quarter of Warsaw, killing or wounding civilians at will, Dinezon and his close friend I. L. Peretz, refused to be intimidated. They walked the streets of their neighborhood determined, as Dinezon wrote, not to be cornered like rats in their hole.

In the face of great threat and difficulty, Dinezon refused to leave his friends or his people.

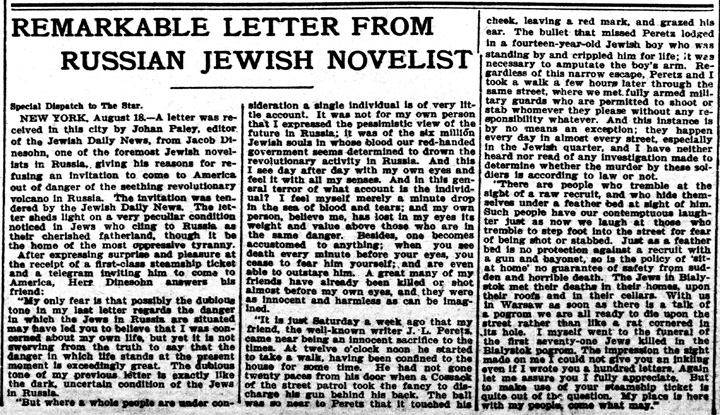

Here is Dinezon’s letter as published in the Washington Sunday Star:

Special Dispatch to The Star

New York, August 18. — A letter was received in this city by Johan Paley, editor of the Jewish Daily News, from Jacob Dinesohn, one of the foremost Jewish novelists in Russia, giving his reasons for refusing an invitation to come to America out of danger of the seething revolutionary volcano in Russia. The invitation was tendered by the Jewish Daily News. The letter sheds light on a very peculiar condition noticed in Jews who cling to Russia as their cherished fatherland, though it be the home of the most oppressive tyranny.

After expressing surprise and pleasure at the receipt of a first-class steamship ticket and a telegram inviting him to come to America, Herr Dinesohn answers his friend:

“My only fear is that possibly the dubious tone in my last letter regarding the danger in which the Jews in Russia are situated may have led you to believe that I was concerned about my own life, yet it is not swerving from the truth to say that the danger in which life stands at the present is exceedingly great. The dubious tone of my previous letter is exactly like the dark, uncertain condition of the Jews in Russia.

“But where a whole people are under consideration, a single individual is of very little account. It was not for my own person that I expressed the pessimistic view of the future in Russia; it was of the six million Jewish souls in whose blood our red-handed government seems determined to drown the revolutionary activity in Russia. And this I see day after day with my own eyes and feel it with all my senses. And in this general terror, of what account is the individual? I feel myself merely a minute drop in the sea of blood and tears; and my own person, believe me, has lost in my eyes its weight and value above those who are in the same danger. Besides, one becomes accustomed to anything; when you see death every minute before your eyes, you cease to fear him yourself; and are even able to outstare him. A great many of my friends have already been killed or shot almost before my own eyes, and they were as innocent and harmless as can be imagined.

“It is just Saturday a week ago that my friend, the well-known writer I. L. Peretz, came near being an innocent sacrifice to the times. At twelve o’clock noon, he started to take a walk, having been confined to the house for some time. He had not gone twenty paces from his door when a Cossack of the street patrol took the fancy to discharge his gun behind his back. The ball was so near to Peretz that it touched his cheek, leaving a red mark, and grazed his ear. The bullet that missed Peretz lodged in a fourteen-year-old Jewish boy who was standing by and crippled him for life; it was necessary to amputate the boy’s arm. Regardless of this narrow escape, Peretz and I took a walk a few hours later through the same street, where we met fully armed military guards who are permitted to shoot or stab whomever they please without any responsibility whatever. And this instance is by no means an exception; they happen every day in almost every street, especially in the Jewish quarter, and I have neither heard nor read of any investigation made to determine whether the murder by these soldiers is according to law or not.

“There are people who tremble at the sight of a raw recruit and who hide themselves under a feather bed at the sight of him. Such people have our contemptuous laughter just as now we laugh at those who tremble to step foot into the street for fear of being shot or stabbed. Just as a feather bed is no protection against a recruit with a gun and bayonet, so is the policy of ‘sitting at home’ no guarantee of safety from sudden and horrible death. The Jews in Bialystok met their deaths in their homes, upon their roofs and in their cellars. With us in Warsaw, as soon as there is talk of a pogrom, we are all ready to die upon the street rather than like a rat cornered in its hole. I myself went to the funeral of the first seventy-one Jews killed in the Bialystok pogrom. The impression that sight made on me I could not give you an inkling even if I wrote you a hundred letters.

“Again let me assure you that I fully appreciate your offer, but to make use of your steamer ship ticket is quite out of the question. My place is here with my people, come what may.”

Library of Congress. Chronicling America. Evening Star. August 19, 1906. Page 5. Image 17.